Wild fantasies of the familiar kind

A retrospective show of works by South Korean comic art maestro Kim Jung-gi illuminates the artist's gloriously bizarre creative universe, where love and empathy can blossom in the most sordid of conditions. Chitralekha Basu reports.

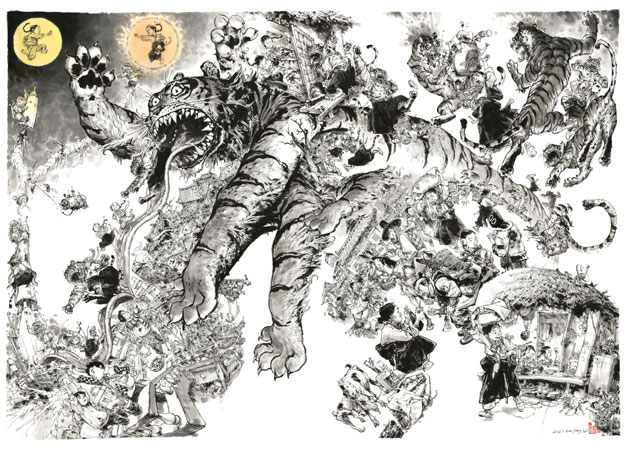

An enormous tiger, brandishing an excess of canine teeth and predatory paws, threatens to leap out of the canvas. The image packs an entire narrative into a single frame. In this pictorial re-telling, a time-tested Korean folk tale — about how a young brother and sister escape the clutches of a pursuing tiger by turning themselves into the moon and the sun — is relocated to a recognizable, semi-urban contemporary setting. The mother of the brother-sister duo holds onto a disposable cup as she squats down with her ware next to a coffee machine at the marketplace. The thatched roof of the family's modest little patchwork house is fitted with a satellite TV antenna. As the siblings run for their lives, sliding down the tiger's enormous tongue, the sister films the beast - emerging from its own mouth — coming after them.

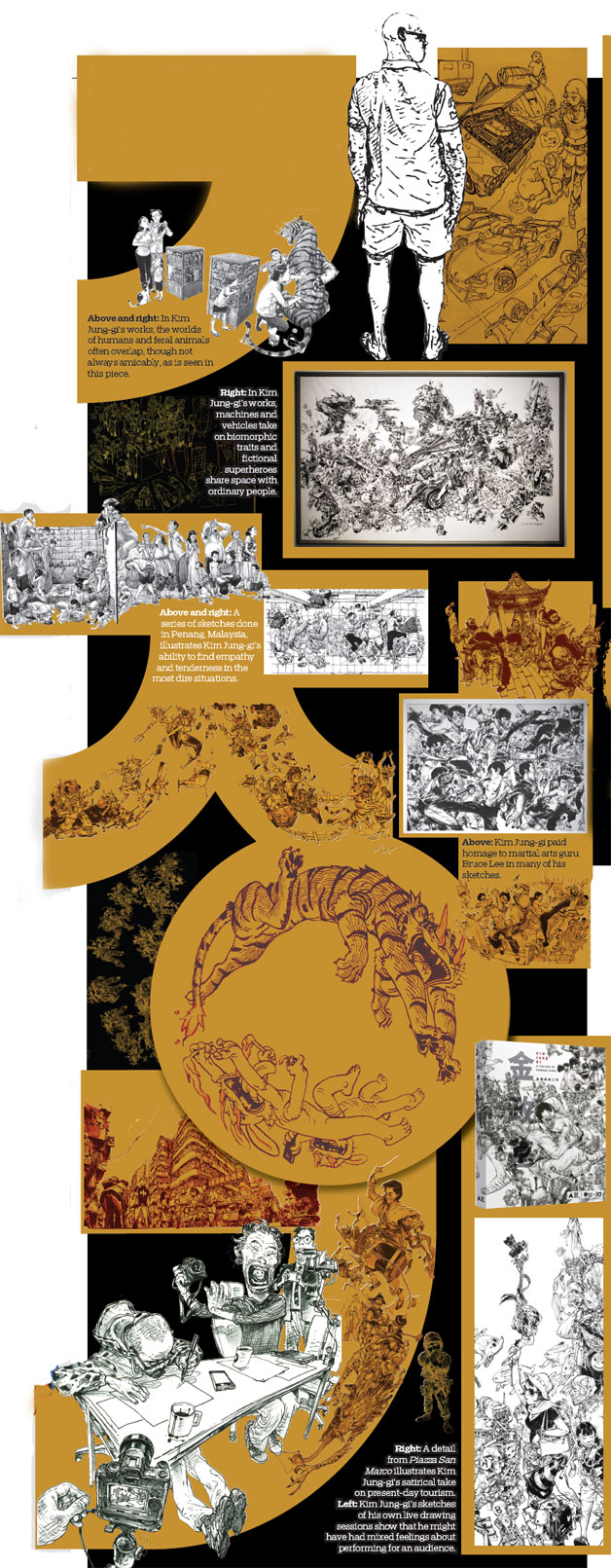

Welcome to the world of South Korean comic artist Kim Jung-gi (1975-2022). In his works tradition, history, mythology and a slow-paced and simpler way of life exist side by side with urban excesses — masses of tangled cables spilling out of car engines like human entrails, for example. Headphones, mobiles and hand-held cameras, attached to human body parts like prosthetic extensions, are too numerous in Kim's works. The image of a tourist using a bird's tied-up legs like an overhead camera rig — a tiny detail from the 2.5-by-1.4-meter work called Piazza San Marco — conjure up a bizarre, fantastical universe that is also soberingly familiar.

Kim's wider international recognition is largely owed to his large-scale ink artworks, often drawn live — without a preliminary sketch or any other form of reference — in front of an audience. A number of these are on show for the first time in Hong Kong, as part of a retrospective exhibition, Kim Jung Gi: A Journey to Endless Lines, at the Hong Kong Arts Centre.

Delicious chaos

Kim was almost exclusively into sketching the intricate designs of guns and military vehicles when he started out as an artist. He had served in the South Korean Army and seemed to have an obsessive interest in drawing scenes of the battleground. The artist's long-time associate and exhibition curator, Kim Hyun-jin says, "He had started out by drawing weapons, and then moved on to motorcycles and cars. In his drawings, human figures often take on forms similar to a motorcycle in motion."

The artist clearly enjoyed throwing wild animals, human beings and machines together, often into an inextricably tangled web. In his creative universe, combat vehicles barrel through a battlefield like a mythical beast with webbed wings and rapacious claws, while elsewhere, cherubs with sewing machines for wings seem to be randomly sewing together masses of human flesh, as if to make a patchwork carpet.

Bandages seem to be the most ubiquitous leitmotif, apart from weapons and vehicles, freely applied on human figures, machines, and in one instance to the back of a tiger inspecting the medical procedure with a benign smile.

Apparently, Kim's world of bizarre juxtapositions is falling apart, but it is also under repair.

Kim Hyun-jin says that the artist's no-holds-barred depictions of sordidness - and there are several of the kind in the exhibition, be it of violence or squalid and abject poverty - stemmed from his acknowledgment of the hard realities of life. "He believed that nudity is not something to hide as that's how we all are under our clothes," Kim Hyun-jin says. "But there is also the presence of good, even if it is surrounded by festering poison."

A pair of drawings depicting street scenes in a grungy, run-down part of Penang, Malaysia, illustrates his point. One of these shows the interiors of a public washroom-cum-lavatory, with a bunch of people already inside while a queue of wannabe-users desperate to get in forms outside the door. Viewers can almost smell the stench.

The other is a bird's-eye view of people sleeping rough on a tiled pavement strewn with newspapers. One of the sleepers, possibly in a moment of soporific ecstasy, hits a fellow sleeper's face with his big toe, while a motherless child tries to find comfort by snuggling up to his father's exposed breast.

Love song to Hong Kong

Hong Kong figures noticeably in the exhibition. Original artworks from the comic book Spy Games — for which the artist collaborated with writer Jean-David Morvan — are on display. The art deco buildings on Nathan Road, the neon-sign-embellished congested street scenes of Mong Kok, and the close-knit public housing estate buildings rising like a mountain range and obscuring half the sky in Quarry Bay are instantly recognizable. There is also Bruce Lee resisting a pack of adversaries with his infallible moves.

Interestingly, the artist never set foot in Hong Kong. "He knew about Hong Kong landscapes because he grew up watching a lot of Hong Kong movies," says Kim Hyun-jin. "During his young days, Hong Kong was considered the epitome of elegance and sophistication — a city that had touched the pinnacles of fashion and films — in South Korea, hence he was fascinated by Hong Kong culture."

Free spirit

Kim Jung-gi sounds like someone who was not particularly concerned about leaving behind a lasting legacy. According to Kim Hyun-jin, the artist "did not think much about the artistic choices he made, not as much as people would expect him to".

Apparently, the artist took neither his work, nor himself, very seriously, promising to quit the day he stopped enjoying making art. The few self-portraits in the exhibition show him as either being sliced and quartered, revealing machine parts inside his sectioned body, or grimacing at his own public performances, clearly with mixed feelings about playing the performing monkey.

Kim Jung-gi had warned wannabe artists against trying to imitate his style or method.

"He believed artists should do what they really like and not think too much about it," says Kim Hyun-jin. "But he also believed in hard work and that his own success was due to his investing an astounding amount of time and energy in his practice."

Contact the writer at basu@chinadailyhk.com

- Wenchang Aerospace Science and Education Center upgrade nears completion

- Chinese Navy hospital ship completes medical service to Fiji, heads for Tonga

- Visa-free entry policies boost inbound tourism during National Day holiday

- Two giant pandas debut after quarantine in Beijing

- From a large landfill to a digital innovation valley

- Taiwan leader denounced for separatist plot